As Sr. Director of Adoption and Engagement for Community Cloud, I spend a lot of time developing best practices and strategies to help customers improve their community’s business value. Having met with many of our customers to discuss their community goals and objectives, I'd like to share some key takeaways about community strategy with you in this three-part series that includes:

• Shared purpose — creating meaningful connections with customers

• The BIG, big picture — managing communities at scale

• Launch — what it takes get a successful community off the ground

This is the first post in that series.

I spoke about these strategies in a breakout session at Dreamforce ’16. One of the thought leaders who joined me onstage was Charlie Brown, CEO and Founder of Context Partners, who spoke about shared purpose in communities.

Cesar: In my role I like to emphasize the non-technical, strategy side of driving community success, which is a good complement to the capabilities and power of the Salesforce platform. In conversations with dozens and dozens of customers during my time at Salesforce, I’ve learned a few things about what makes for engaged communities. I want to share some of these observations, jointly with Charlie Brown, Founder of Context Partners. Charlie and I have had the opportunity to tell this story both at Dreamforce and in a recent webinar where we discussed this very topic of engaged communities. I think Charlie’s perspective here is very valuable and recently we discussed his point of view on this topic.

Charlie, what has inspired you to develop these observations on engaged communities?

Charlie: If you’re using or considering a platform like Salesforce's Community Cloud, you already understand the benefits of having an engaged community: a better customer service experience, more social media buzz, more durable customer relationships, and in many cases, a source of innovation. But you’ve also seen “community” sometimes relegated to buzzword status, slapped onto existing efforts to give them a whiff of novelty and legitimacy. For many organizations, community is something executives are excited to talk about and maybe even purchase software to support, but when it comes to a robust network strategy, there’s less follow-through.

At its most basic level, a community is simply a group of loosely connected people. For businesses, we tend to assume that those connections are sales-related — or at least the connections we care about are. This is why our CRMs tend to be filled with an ever-growing volume of leads and contacts whose commonalities are vague at best, and who may not even think of themselves as a community.

If the only thing connecting people is transactions, they’re not very engaged. Far more robust and innovative communities share something deeper, and there’s great value to be found in becoming a tightly organized, well-managed network. Helping organizations — whether small nonprofits or Fortune 100 corporations — make this transition is what Context Partners has done for the past several years. In that time, we’ve come to recognize three features that show up in every successful community engagement effort: shared purpose, six aspirational roles, and effective incentives.

Cesar: Excellent, let’s start with shared purpose. I’ve heard that term before — how would you describe it?

Charlie: A common mistake we see when it comes to shared purpose is putting your organization’s goals at the center of the community. Far more often, your community is connected by a shared purpose, of which your organization is a part. Begin by finding out what that purpose is.

Patagonia is a brand with a powerful, engaged community, but the purpose that connects its members isn’t “I love Patagonia.” It’s “Live Simply”: a purpose that incorporates outdoor activity, environmental activism, and almost tangentially, the few pieces of well-made apparel and equipment people take with them on their adventures.

Like any effective shared purpose, “Live Simply” transcends the organization’s mission and vision, and taps into something the Patagonia community was already doing in a looser, more isolated fashion. The message is clear and concise enough to fit on a T-shirt (or sweatshirt, in Patagonia’s case). This shared purpose is why Patagonia has been able to double its revenue over a five-year period while working to block threats to the wild places they’re so passionate about.

Cesar: What advice would you give to community professionals who want to develop a shared purpose for their communities? I’ve often heard it described as something you do with your community.

Charlie: Absolutely. My advice to community professionals would be, before you start making grand statements and plans about your community, ask yourself: What is the shared purpose that connects me with my customers, employees, and contacts? What is the larger aim that brought us together in the first place?

Cesar: Now let’s shift the discussion to roles. Your point of view on roles is very interesting, especially how you talk about going beyond demographics.

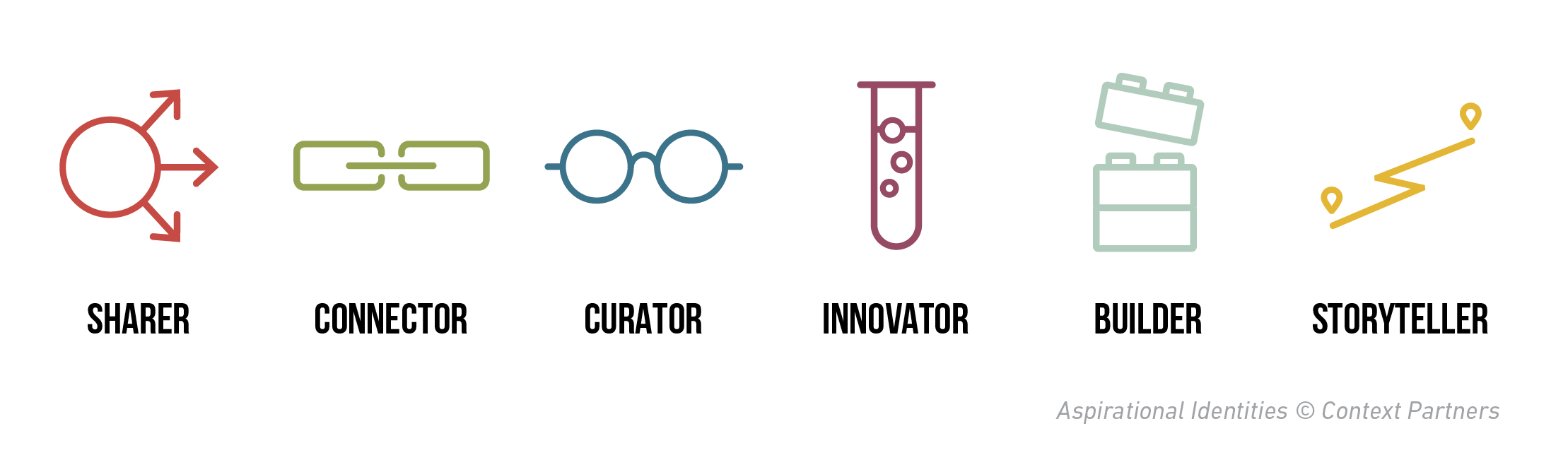

Charlie: Another common mistake we see is when community members are organized solely by demographic or purchasing data. I believe in understanding the six key roles that community members aspire to, and developing analysis tools to identify and engage with them.

Cesar: Can you give an example?

Charlie: We recently did this with a leading global technology company to build their loyalty program. When we asked who their community was, they gave us a database of 1.2 million customers who had signed up, but little else. After a survey investigating reasons for brand loyalty, and a series of follow-up interviews, we were able to categorize those customers according to the six aspirational roles we've uncovered in all successful networks:

● Builder — Brings order and structure

● Innovator — Tinkers with existing systems, finds connections

● Curator — Finds and collects the best of what’s being created

● Connector — Knows others’ needs and abilities, and joins them together

● Sharer — Listens and communicates in high volumes

● Storyteller — Motivates and unifies with observation-based narrative

Mapping these roles against the company’s core business goals, we realized the company wasn't connecting with the right members. Not surprisingly for a tech firm, its community mostly consisted of builders, a few innovators, and few others.

But their leadership was looking to increase brand advocacy (a connector and sharer activity), develop new features and products (an innovator activity), and create user-generated marketing content (fun for storytellers and curators). This explained why they’d been struggling to make headway — they were seeking engagements that only part of the community wanted. What they needed was a clear strategy, starting with a taxonomy of desired traits in community members, and an integrated CRM specifically designed to identify and nurture them.

Most organizations habitually sort community members by demographics and transactional roles: how old, how urban, how much income, how often they make a purchase. But the distinctions that truly matter for community building are aspirational roles that cut across demographics — a storyteller could be a 47-year-old working mom who’s a loyal customer, or a 19-year-old male with no disposable income to speak of. How do you identify the traits that reveal the aspirations in your community, and design strategies for empowering them?

Cesar: That’s very practical advice. I also think that by defining roles in the manner in which you describe, you can more effectively tailor reward and recognition programs based on roles, and not necessarily treat the community as a single, homogenous group. In general, what recommendations do you have around incentivizing community members?

Charlie: We often are asked to provide advice on structuring incentive programs, and one common mistake we see is attempting to motivate community members exclusively through material rewards, which rarely build engagement in the long term. A discount or a free iPad might grab attention, but once received, it’s quickly forgotten. We think it’s better to learn from the behavioral science community, which has repeatedly found that recognition and experiential rewards are far more effective at shaping new habits.

That tech company client of ours had an incentive system built entirely around material rewards. The company paid community members for identifying bugs or responding to customer questions, and even offered discounts just for clicking through on a mass email. Not surprisingly, none of these tricks did much to nudge anyone toward the company’s longer-term goals.

It turned out that active community members were much more interested in things like early product releases, certifications that raised their status within the community and on their LinkedIn profiles, and special-event lounges where they could access exclusive projects. Each of these has little explicit monetary value, but they’re very responsive to the members' specific interests. Anyone can win an iPad; active community members want something that recognizes their unique value.

Putting real thought into the kinds of rewards your community will truly value is a hallmark of successful community-oriented companies, from Airbnb and eBay to Tesla and Tom’s. What kind of experiential and recognition-based rewards are most likely to resonate with the people in your CRM?

That technology company shifted direction, applying the principles above to create a well-managed network strategy. The result: a seamless customer experience coordinated among 16 different departments, and community growth from 1.2 million to 5 million members in under six months. Moreover, that community is now an organized army of advocates, evangelists, and feedback providers, generating higher levels of new product buzz and home-grown social media engagement than ever.

Cesar: Just to add to your point, I remember when I used to work at InnoCentive, one of the early pioneers in challenge-based innovation, we learned that the desire to be recognized as a successful problem-solver was as strong or stronger than the associated monetary reward that came with solving the challenge. This was somewhat unexpected and it forced us to rethink our incentive strategy. We didn’t drop the monetary rewards, we did change our assumptions around what motivated people to work on these challenges. Any closing thoughts?

Charlie: If we all agree that “community” is more than a word, we have to acknowledge that it deserves a real strategy, not just a software solution. CRM is usually seen as a pathway to efficiency, but a CRM by itself can’t make you a leader in the relationship revolution. Used in tandem, however, with a smart incentive system, a clear understanding of your community’s roles and a well-defined shared purpose, it can transform your entire organization.

CONCLUSION:

I hope you enjoyed this conversation. Be sure to check back for the next post in this series, when I’ll talk with Erica Kuhl, Vice President Community at Salesforce, about managing communities at scale.

If you want to learn more: