Getting funding for your business venture may be one of the most frustrating processes you ever face. By the end of the journey, venture capitalists may remind you of ruthless people who take pleasure in your butterflies and like to see you experience dread when your dreams are on the line. The truth is more nuanced: These people are just trying to be the best in their business, too.

The job of a venture capitalist, or VC, is to bring lucrative deals to their investors. That’s the end goal. To do that, they need to thoroughly vet every single venture they fund. They look for investments with the highest possible return and the least possible risk.

On the surface, it’s a simple equation: Rewards must be greater than risks. In practice, it’s nearly impossible to predict how a company will do once funded. Some VCs have a specific, tried-and-true formula they use to evaluate risk and reward. In fact, Clint Korver created his own software to do just that. But either way, most venture capitalists have the same basic approach.

The Risk

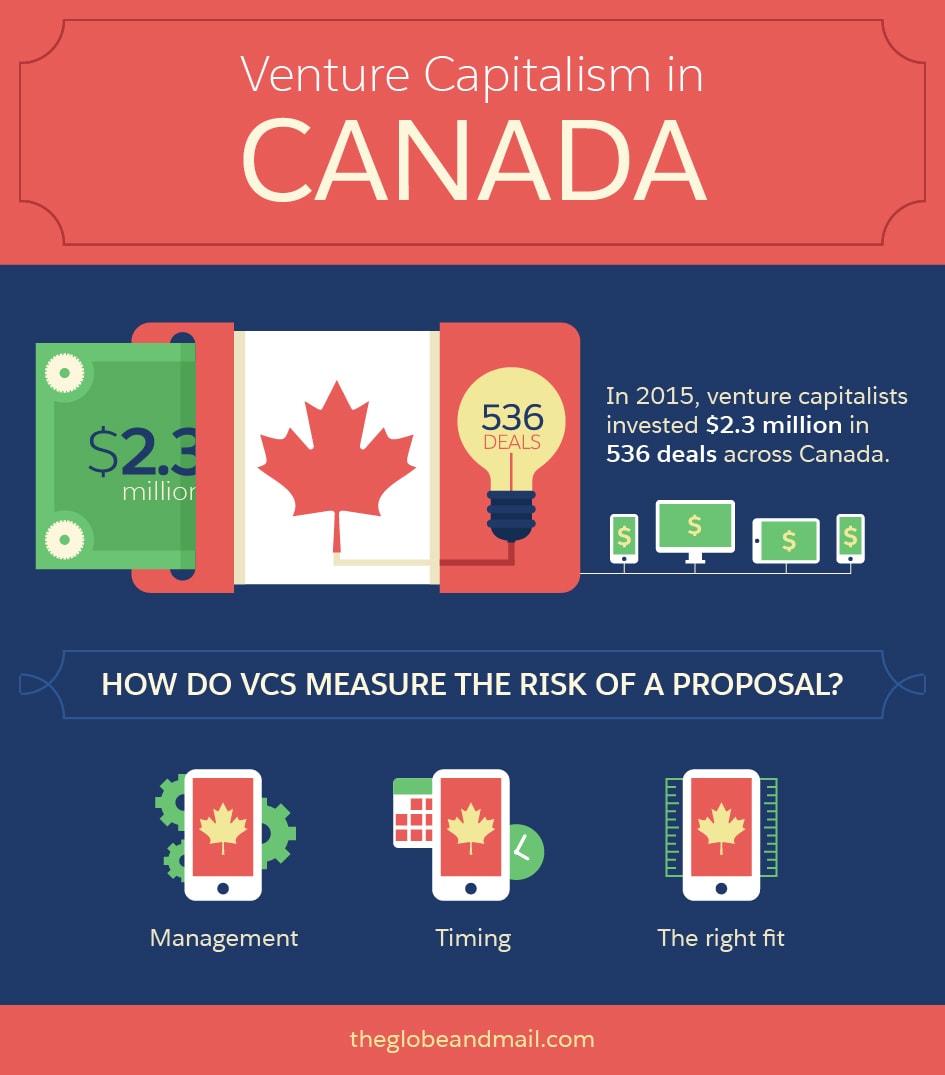

In 2015, venture capitalists invested $2.3 million in 536 deals across Canada. So there’s plenty of capital to go around, right? But although according to one study, Canada is the second most entrepreneurial country (right behind the United States), venture capitalists can’t fund everything. And they wouldn’t want to, not with a nationwide average success rate of just 50 per cent. Instead, VCs focus on projects that present the lowest risk.

There are plenty of things that can sink a business. Many are completely unpredictable. Some of them, however, may be inherent in an organization.

Venture Capitalism in Canada

- In 2015, venture capitalists invested $2.3 million in 536 deals across Canada

- How do VCs measure the risk of a proposal?

- Management

- Timing

- The right fit

Management

What do most venture capitalists see as the riskiest part of most ventures? Chances are, it’s you, the management. That’s why most investment deals are contingent on VCs having one or more seats on your board of directors.

Anyone, like that kid with the lemonade stand down the street, can start a business. But it takes more than an MBA and a passion for cooking to run a successful restaurant, and more than good salesmanship and banking skills to be a CEO. Venture capitalists look for opportunities brought to them by people who have a track record of success in business, the proposed industry, and the market. (That, or one heck of a concept and the willingness to step down and let someone more experienced run the show.)

One of the first things the VC will do is investigate you. Does your CV show a track record of successful startups or highly profitable companies? Have you already worked in the industry you’re asking them to fund? Who’s on your team and how well do they work together? Are there holes in your team that need to be filled before you’re likely to be successful?

Part of a VC’s strategy for investigating you and your team will be your online presence. They’ll also ask colleagues about you as an individual—whether they’ve heard of you, what it’s like to work with you, and how well you’re respected. VCs will also want to get to know you in person at meetings, over drinks, while swinging a golf club: in short, situations where you can impress them with your grit, experience at handling stress, knowledge, or just your ability to schmooze. A good executive needs all of those things.

Timing

Is your product or idea simply wrong for right now? If you’re working on a revolutionary new CD player or an app for self-driving car owners, venture capitalists might be wary.

In the case of the CD player, your product will probably hit the market too late. Sure, people still use and buy CDs, but that technology is on the way out. Even if being completely obsolete is still years away, you won’t have time to turn a profit before what’s left of your market has moved on to smart devices and streaming apps.

In the case of the self-driving car app, you run the risk of hitting the market too early. If it arrives before there are any self-driving car owners, you’ll waste money waiting for your market to exist. And what if legislation shoots down self-driving cars before they even hit the road? At this point, a VC might look over your business idea, but you’ll probably hear, “I’ll call you when I own a self-driving car,” as they tuck your proposal into their files.

Venture capitalists will analyze your current market as well as what that market is likely to do in the future. If they don’t get a clear picture of a market ripe for the picking around the time you expect to have a product ready, don’t expect a term sheet from them.

When is the right window to seek capital for your company? A good rule of thumb is that a business needs at least three years to become profitable. But if you need funding for extensive R&D or lots of equipment up front, it could take much longer. VCs look for timetables that are reasonable for your industry and match investor expectations.

The Right Fit

Sometimes it’s not you. Sometimes it’s them. Venture capitalism is a risky business, so investors tend to diversify. If a VC already has a shoe-manufacturing company in their portfolio, it may not matter how much better your shoes are than the competition’s. They won’t risk putting all their pennies in one piggy bank.

Know that in an investor’s experience, some sectors simply tend to do better than others. For example, VCs invested more money in tech and communications deals than all other sectors combined in 2013, 2014, and 2015.

The Reward

Risk is inherent in any business. In the world of a venture capitalist, there is no “sure thing.” How much risk an investor is willing to take on depends on the other half of the equation: the rewards. The greater the potential for a high return, the more risk they will allow.

The Basics of Calculating the Valuation of Your Startup

- In the early stages, the value of the company is close to $0

- The valuation has to be a lot higher

- The valuation does not show the true value of the company: it shows how much of the company investors get for their investments

- Your valuation is calculated based on how much money you need and how much you’ll give to the investor

- How much money do you need to grow to a point where

- You will show significant growth

- You can raise the next round of investment

- How much of the company will you give to the investor?

- Can’t be more than 50%. That would leave you (the founder) with little incentive to work hard

- Can’t be 40% because that will leave very little equity for investors in your next round

- Could be 30% if you get a large amount of seed money

- For a small investment, give away 5-20%, depending on your valuation

- How much money do you need to grow to a point where

Your Product’s Potential

Back in the day, Apple might have looked like a pretty risky venture. Two young men working out of their garage to build the first personal computers by hand wouldn’t have inspired much confidence in venture capitalists, even back then. The potential of the product to revolutionize computing and personal technology, however, was undeniable. Which is why, when the duo waved a purchase order for 500 computers at the manager of an electronics store, the man gave them the parts they’d need on credit.

Unlike the electronics store manager, venture capitalists don’t use their own money to invest. But they do get a large cut of the rewards. They spend months vetting deals for their investors, and if those deals don’t pay off they don’t get their cut; instead, they get angry clients and a poor track record. If they can’t see potential in your product for big bucks, they’ll walk away.

Does My Product Have Potential?

That depends. A venture capitalist will want to know:

- Is it easy or inexpensive to produce?

- Are you offering something faster, smaller, cheaper, more convenient, or otherwise better than existing competitors?

- Is there an existing market for this product, or will you have to create one?

- How much of the market share can you expect to take in the first few years? Thereafter?

- Is there a mass market for your product, or does it cater to a small, niche market?

- How easy will it be to scale up your business to larger markets?

- How easy will it be for other companies to enter the market with a similar product?

The big question in a VC’s mind is whether they can reasonably expect to turn a profit that’s competitive or better than other investment opportunities. It’s not just a matter of turning a profit. Remember: If they invest in your company, that means they’ll have to forgo investing somewhere else. That’s an opportunity cost.

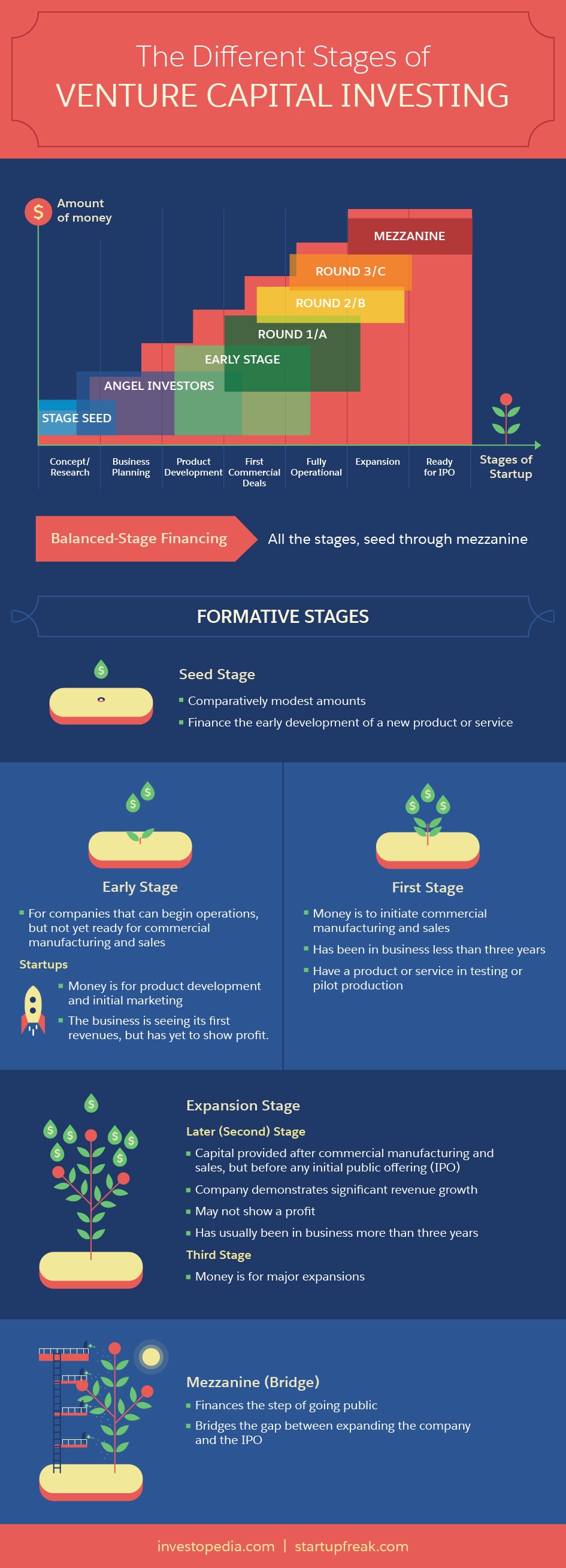

What Stage Is My Company in?

Venture capitalists know that while there are more startups investment opportunities, seed and early-stage companies are riskier than later-stage companies who have proven they can make a profit. VCs make far more deals in seed-stage companies but on average risk less capital. Early-stage companies present less of a risk because they’ve shown they can at least bring a product to market and have some initial success.

The Long Road in Between

As long as rewards are big and existing risks are small, I’ll get funding if I find the right firm, right?

Afraid not.

In between what your company can currently do and what it can become, there’s a long road full of… well, no one really knows. From unforeseen lawsuits and regulations to other companies entering and dominating the market or a breakdown of relationships with platforms you depend on, it’s a perilous world for investors.

Attempting to predict what could negatively affect your business (or simply make it not profitable enough) is what venture capitalists are doing when they spend months or even years doing market studies, investigating your company, and getting to know you. Sometimes there just aren’t answers , which is where a VC’s intuition usually comes into play.

The Different Stages of Venture Capital Investing

- Balanced-Stage Financing: All the stages, seed through mezzanine

- Formative Stages

- Seed Stage

- Comparatively modest amounts

- Finance the early development of a new product or service

- Early Stage

- For companies that can begin operations, but not yet ready for commercial manufacturing and sales

- Start-ups

- Money is for product development and initial marketing

- The business is seeing its first revenues, but has yet to show profit

- First Stage

- Money is to initiate commercial manufacturing and sales

- Has been in business less than three years

- Have a product or service in testing or pilot production

- Expansion Stage Financing refers to the second and third stages

- Later (Second) Stage

- Capital provided after commercial manufacturing and sales, but before any initial public offering (IPO)

- Company demonstrates significant revenue growth

- May not show a profit

- Has usually been in business more than three years

- Third Stage: Money is for major expansions

- Later (Second) Stage

- Mezzanine (Bridge):

- Finances the step of going public

- Bridges the gap between expanding the company and the IPO

- Seed Stage

Statistics Versus Gut Instinct

While there’s no magic formula for finding the perfect investment, venture capital firms often use financial models to make predictions.

The Making of a Model

Financial models are a way to turn uncertainties and qualitative facts into quantitative data. Essentially, the goal is to come up with two sets of numbers:

A. The probability of success

B. If success is achieved, the profit it’s possible to make

Keep in mind, both A and B are sets of numbers.

Finding number set A will include going over every single element of your business plan to decide how probable certain outcomes are. Using the example of a shoe manufacturer, venture capitalists might look at everything from your material supply chains to marketing costs and the number of niche markets you could satisfy. The result will be a series of probabilities that your business will achieve certain milestones, such as early stage success, niche market success, mass market success, and market leader.

Number set B will be estimates of how much profit investors stand to make if and when you hit those milestones. For example, at hitting niche market success, you might expect a return of two times (2X) the original investment. If you become the market leader, you might hit 8X, and so on.

Are You Worth the Risk?

Most venture capitalists already have targets in mind for number sets A and B. If it looks like your company will leave those targets in the dust, you’ll probably get an offer. If you’re nowhere close, you won’t.

But what if you’re close—either a little bit better or worse than their target numbers?

That’s where a VC’s gut comes into play. And it’s where your professionalism, ability to schmooze, and passion for your business come in, too. If you can get just one or two VCs at a firm excited about your company, they could push the deal through.

Your Strategy

Now that you know how a venture capitalist thinks, you can take action. Here’s how you can use that knowledge to increase your chances of scoring funding.

Do Your Own Research and Do It Well

The firm will look you up and down, grill you, and put you to the test. They’ll do their own analysis and research no matter what. But if you can hand them answers to many of their questions before they even start asking, you’ll start to look like you belong in their portfolio. This also gives you the chance to anticipate and address anything that might hold up the deal, like lack of experience or the strength of your competitors.

Know Your Target

Just as a venture capitalist will find out everything he or she can about you, return the favor. The more you know about who you’re dealing with, the better you can maximize your efforts. Do this before you ever approach a firm. You might learn something that makes you not want to work with them. Isn’t that better to know before you select who you’d like to invest in you?

Share "The Process Venture Capitalists Use to Select Their Investments" On Your Site

.jpg)

.png)